Newcastle Archaeology Walk

This page contains the fully referenced contents to the Newcastle Archaeology Walk on the City of Newcastle App. If you would like to do the walk please add the app to your phone via your Android play or Apple store. Click on Menu, then scroll down to Walking Trails and swipe across to the Newcastle Archaeology Walk.

Newcastle Archaeology Walk Introduction

Newcastle has a long and fascinating history. For over 30 years, archaeologists have been uncovering the secrets of Newcastle’s history, resulting in dozens of archaeological reports.

Archaeology is the study of ancient and recent human past through material remains. An example of material remains often found in the Newcastle area are Aboriginal artefacts.

These artefacts help us understand where Aboriginal people camped (Figure 5), what they ate, how they hunted (Figure 6), and where they travelled (Figure 7). It also tells us about the extraordinarily long time Aboriginal people have been in Newcastle. Archaeological evidence (Figure 8) shows occupation dating back over 6500 years, but that is just based on the archaeological sites found so far; the real date is likely much older.

Following the arrival of convicts in 1801, Anglo-European artefacts began to enter the archaeological record in increasing numbers. Examples of these include: bottles (Figure 9), ceramics (Figure 10), shoes (Figure 11), and coins (Figure 12). Other evidence can include structural remains (Figure 13), yard surfaces (Figure 14), and wells (Figure 15).

The material remains are buried in different soil layers named strata (Figure 16), and this allows us to understand when things happen to develop a sequence for the site, also known as chronology.

Archaeological work can be divided into three stages: background research, excavation, and reporting on the results of the excavation.

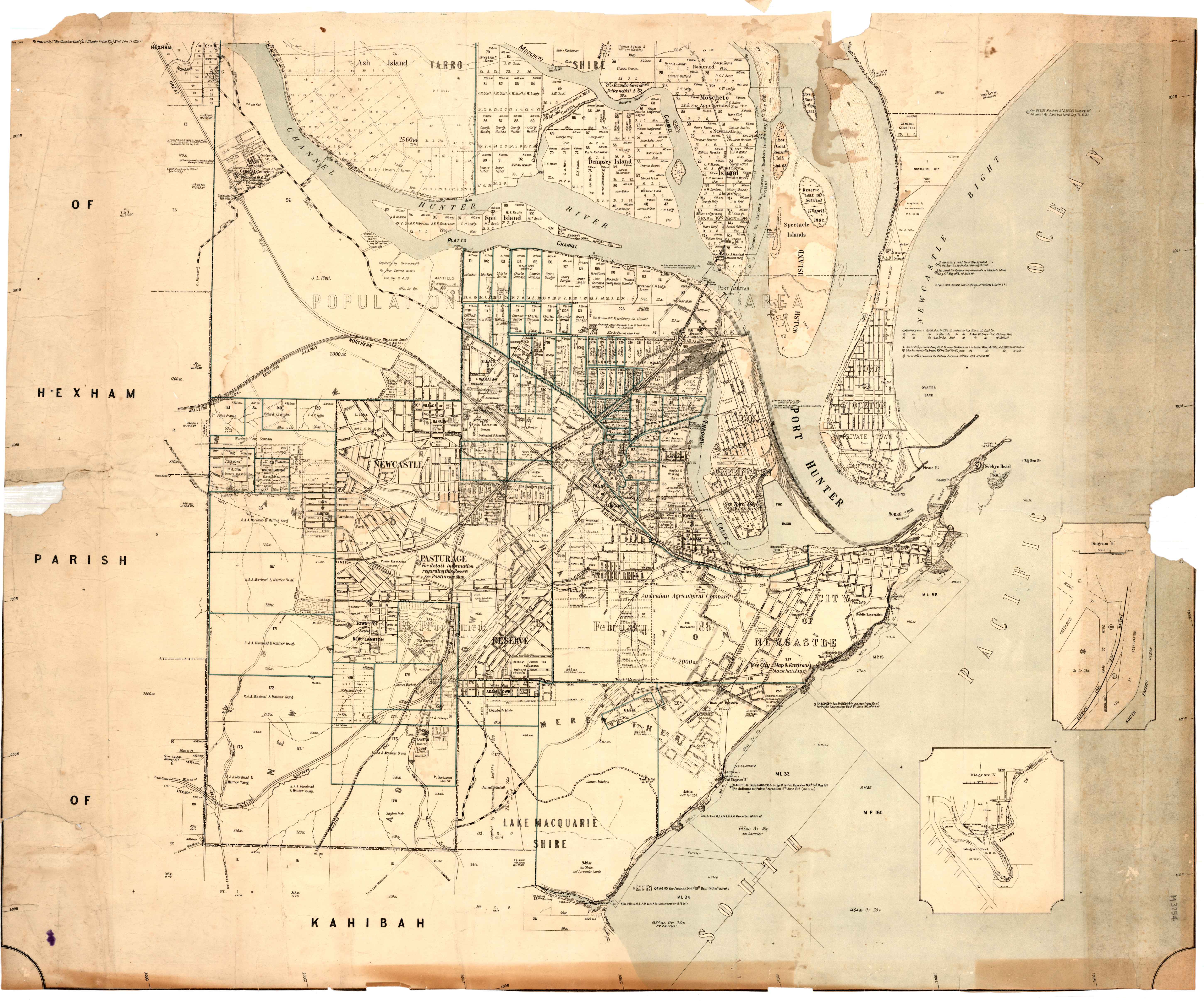

Before archaeologists dig, they do a lot of background research to find out what might be there. This can include reviewing other archaeological reports, collecting information from primary historical sources including newspapers, maps and other records from the time period (Figures 18, 19, 20). Aboriginal stakeholders also provide essential information for understanding landscape patterns and cultural history (Figure 21).

The excavation stage, that is the actual archaeological dig, may be done only by hand or may involve the use of machinery (Figure 22 and Figure 23). Often rectangular or square trenches are dug to provide a sample of the site (Figure 24). Using a trench system allows for detailed recording of archaeological finds both horizontally and vertically.

After the excavation has finished, archaeologists write up their results in a report. This involves the careful tabulation of data, assembly of diagrams, reporting, and interpretation of the archaeological site (Figure 25). While the reports are interesting for archaeologists, they often are very long and data heavy.

This Newcastle archaeological walk seeks to tell the story of archaeological sites in Newcastle and make them come alive.

Archaeological images kindly provided by:

Honeysuckle Foreshore Archaeology

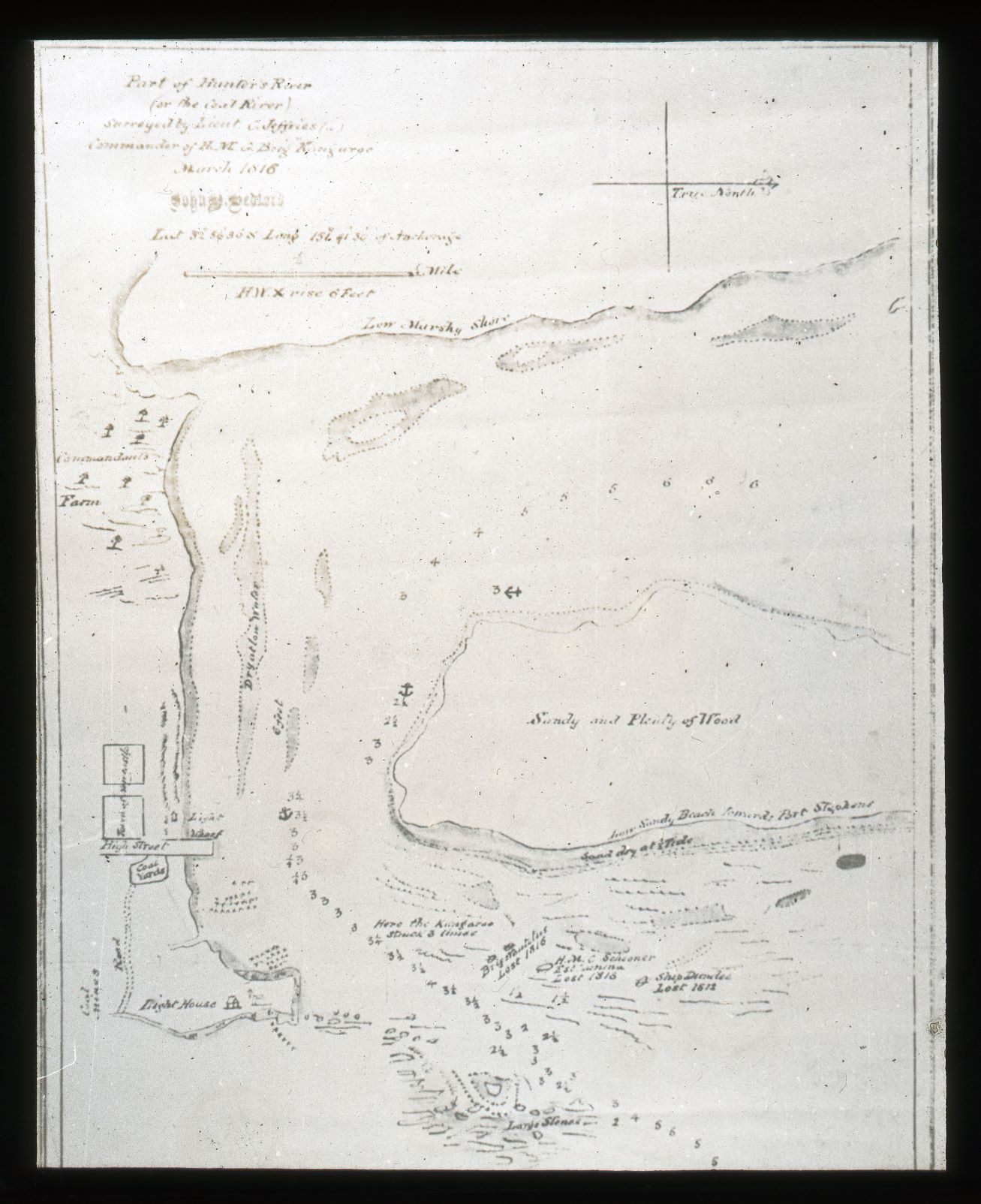

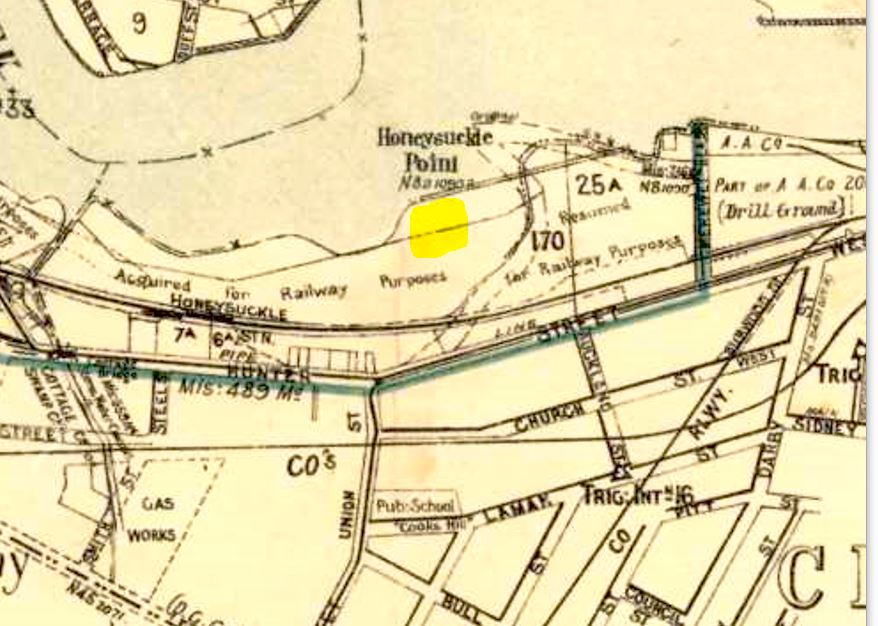

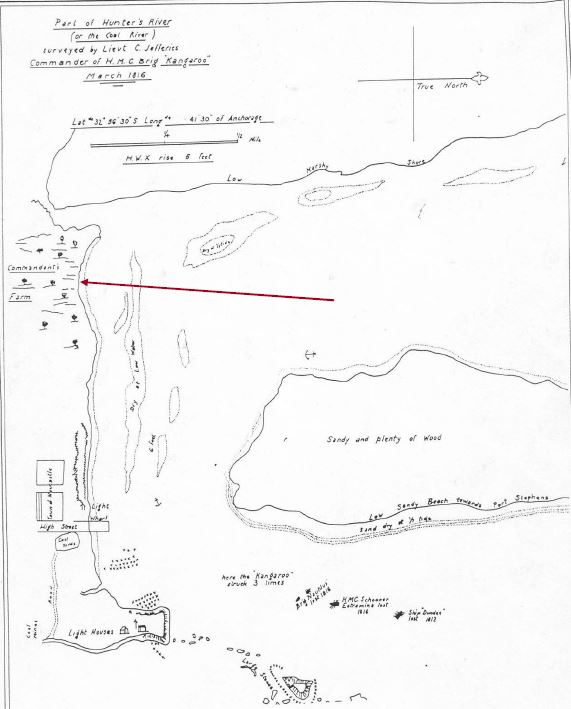

If you were standing right here in 1816, you would have needed very long legs or a boat to keep you dry as this spot was still part of the Hunter River (Figure 26 and Figure 27). 2

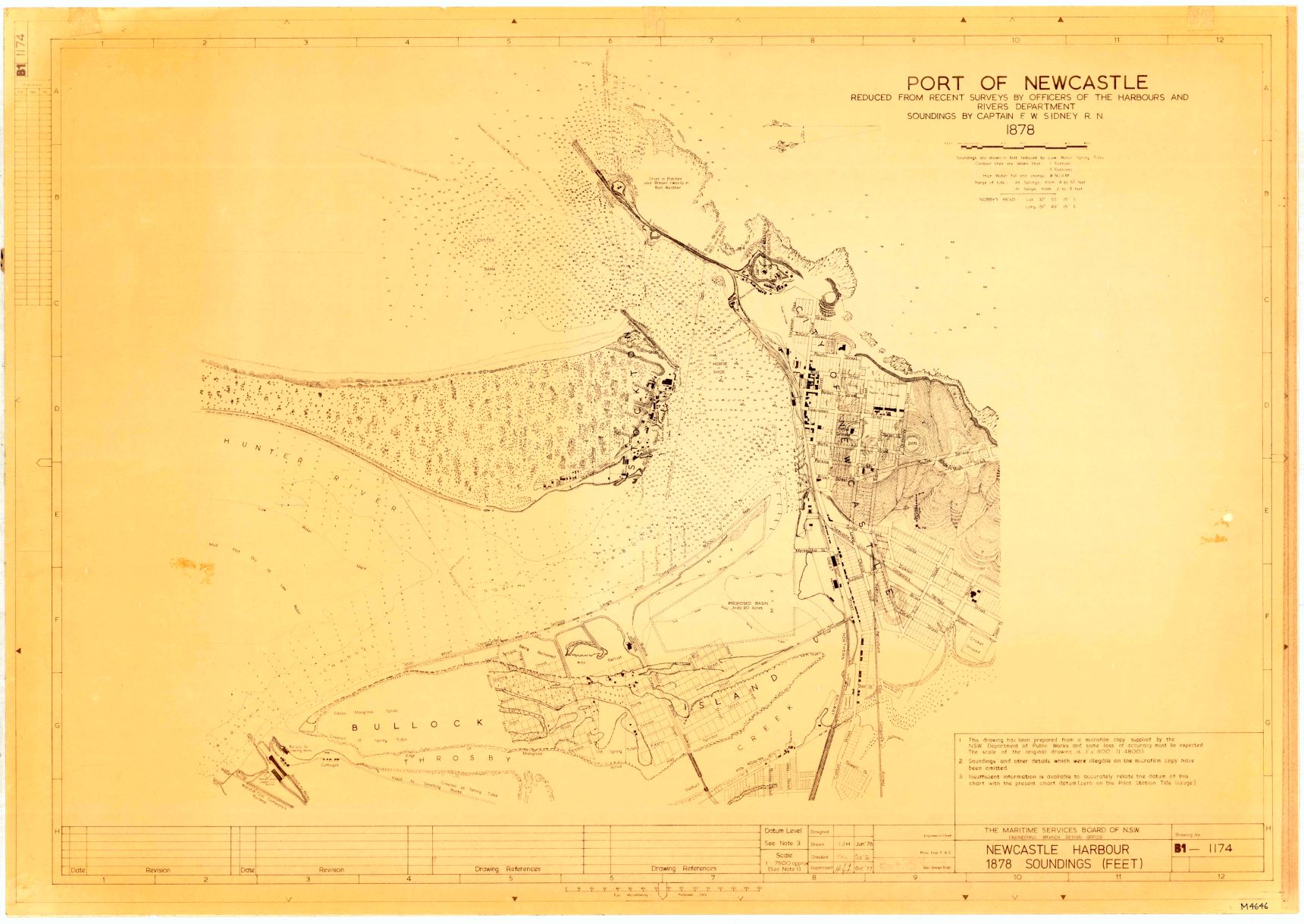

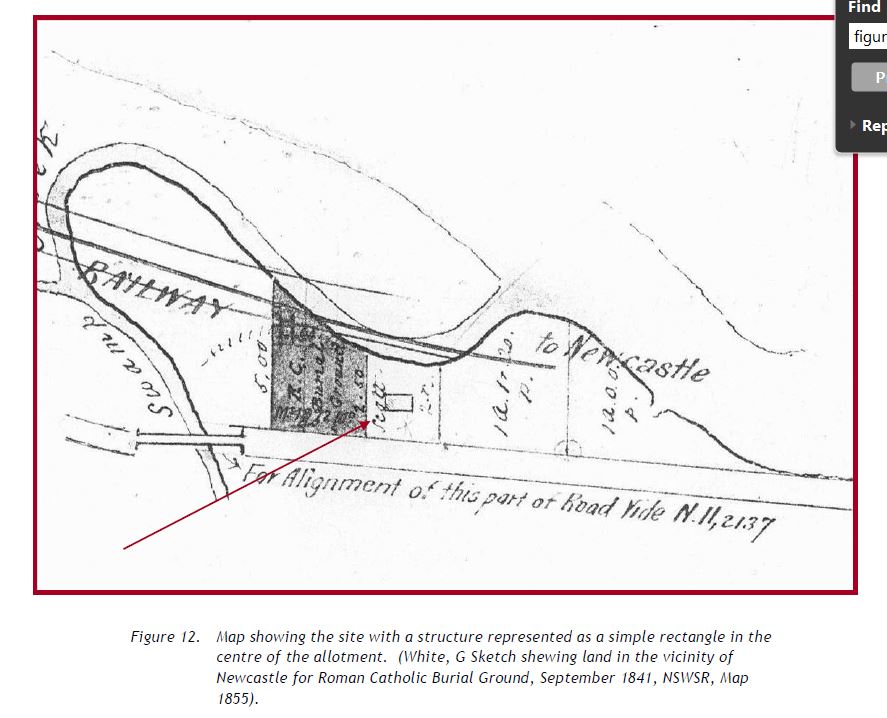

By the mid-1850s, the area directly south of this part of the harbour was reclaimed for a rail line (Figure 28 and Figure 29). 3

This is important because it marked the beginning of a series of harbour infill and reclamation activities that has shaped the harbour we know today. From around 1890, the area known as the Basin was gradually filled in with soil which expanded the land in this area. By 1896, the area south of the rail line embankment was filled in, and by 1920 it was completely filled in to become the foreshore we stand upon today (Figure 30 and 31). 4

The Leo

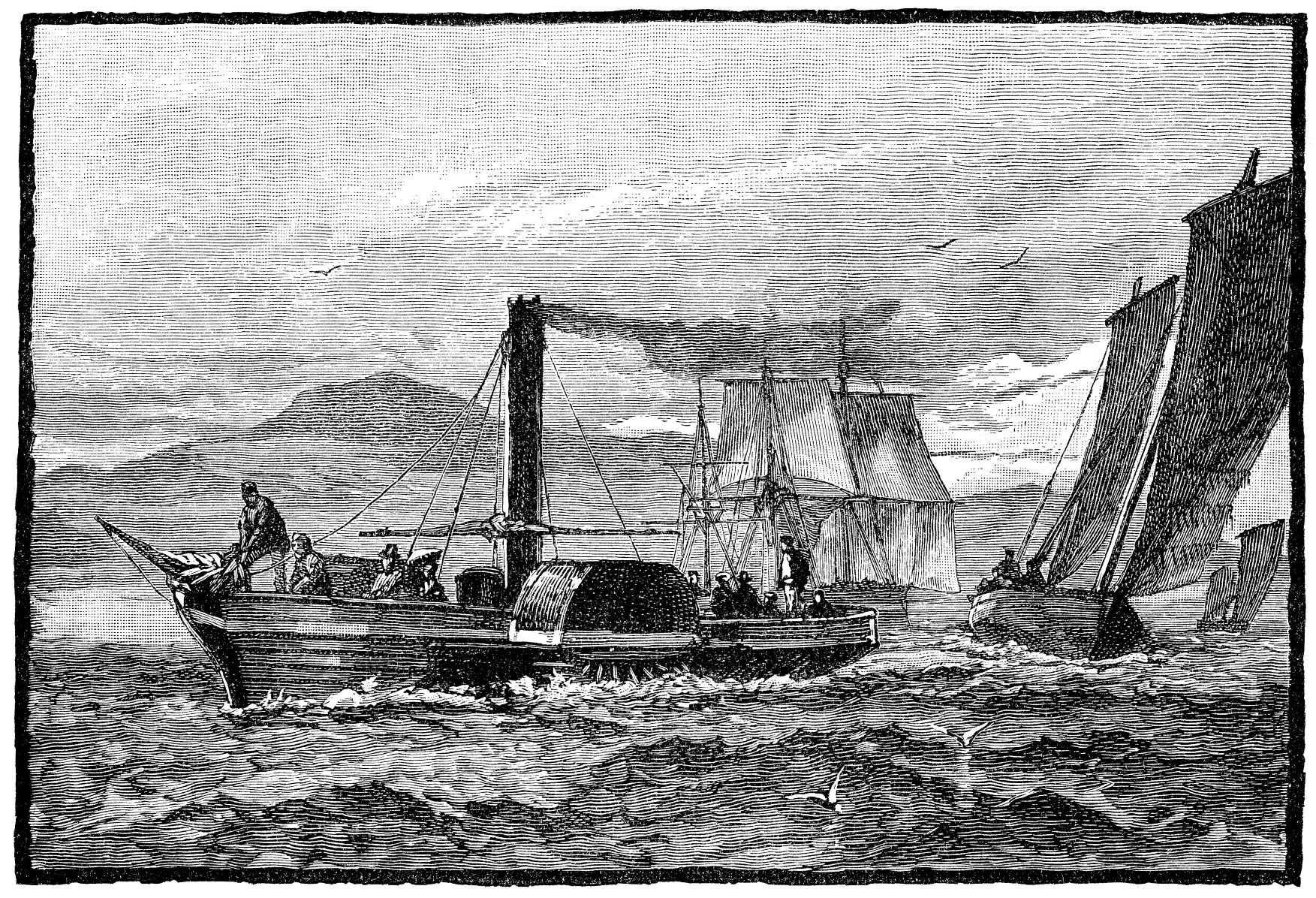

The next part of our story starts in 1871 on the other side of the world in the United Kingdom. In the port city of Bristol, a paddle steamer tug boat was built and named the Leo. While no image of the boat exists, it would have looked similar to this (Figure 32). 5 The boat was a side wheel paddle steamer which was powered by a side lever 56 horse-power engine. The engine had been designed and manufactured in Glasgow, Scotland by Wingate and Co. Although the boat was steam powered, it still had a single mast which could be used to sail the vessel should the engine fail.

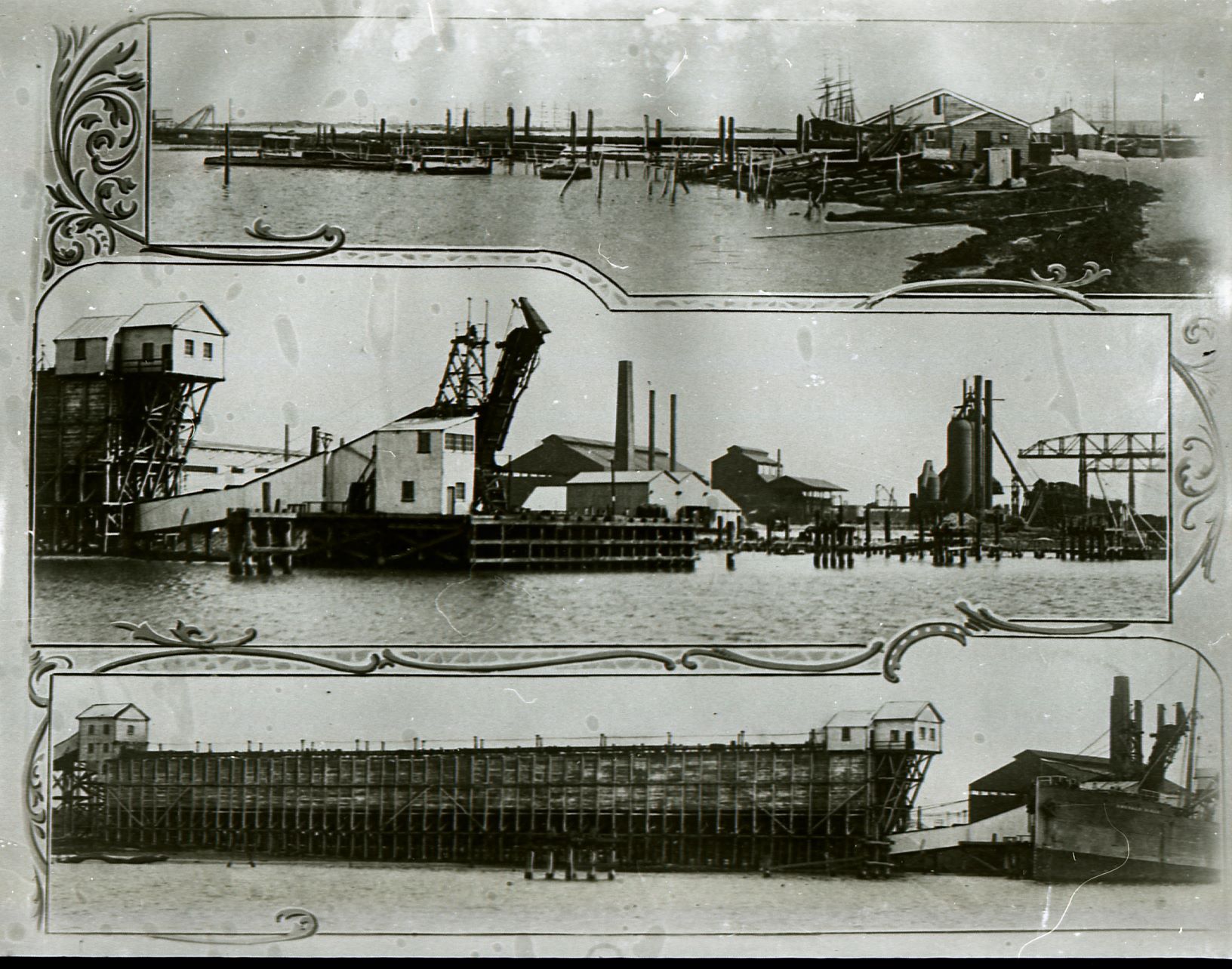

The Leo operated for a number of years in Cape Town, South Africa, before being brought to Australia 1875 by R.B. Wallace of the Newcastle Co-operative Steam Tug Company Limited. One of the newspapers at the time reported the arrival of the Leo, it described it as having “engines of 56 horse-power and has good speed” (Figure 33). 6 Two years later the boat was sold to James and Alexander Brown (Figure 34) 7 who were local colliery owners and entrepreneurs. Things didn’t go so well for the tug-boat, as over the next several years local newspapers reported several collisions and accidents involving the Leo and other vessels in the harbour. One of these involved a collision with the inward-bound steamer the Boomerang (Figure 35) 8 from Sydney in 1879, and another in 1881 when the Leo collided with the Bonnie Dundee.

Despite this, the Leo successfully assisted a number of vessels around the harbour’s entrance with one of the more notable being the schooner the Atlantic. The Leo was last registered with J. and A. Brown in 1883 and then appears to have been bought by BHP around 1915 (Figure 36). 9

This information is contained in the BHP records, but not in the shipping register. This suggests that the Leo by this time was a hulk, which means it was no longer a seaworthy vessel and likely was just used for transport only within the harbour. The register for the Leo was closed in 1917 and its final fate remained a mystery…..until 2007, when archaeological works began as part of the redevelopment of the Honeysuckle precinct.

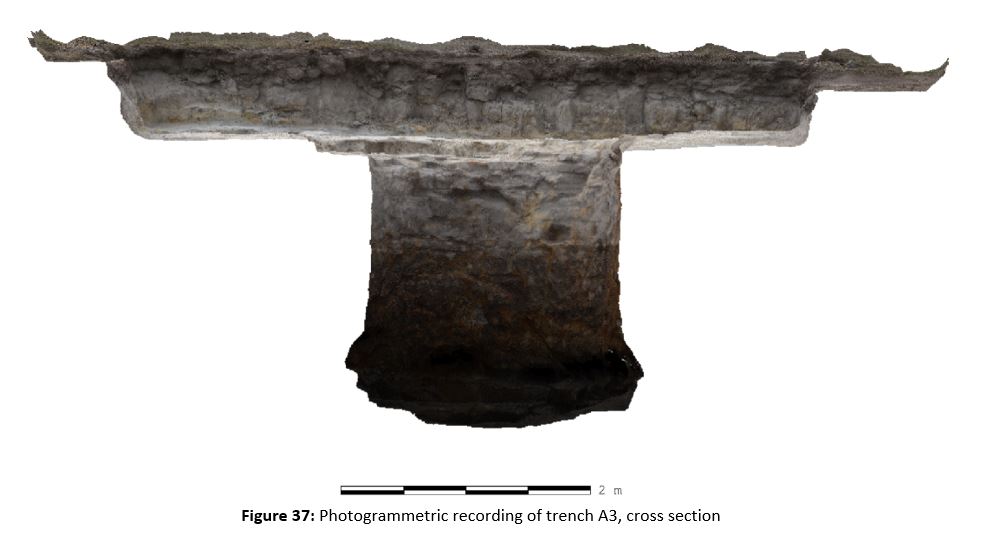

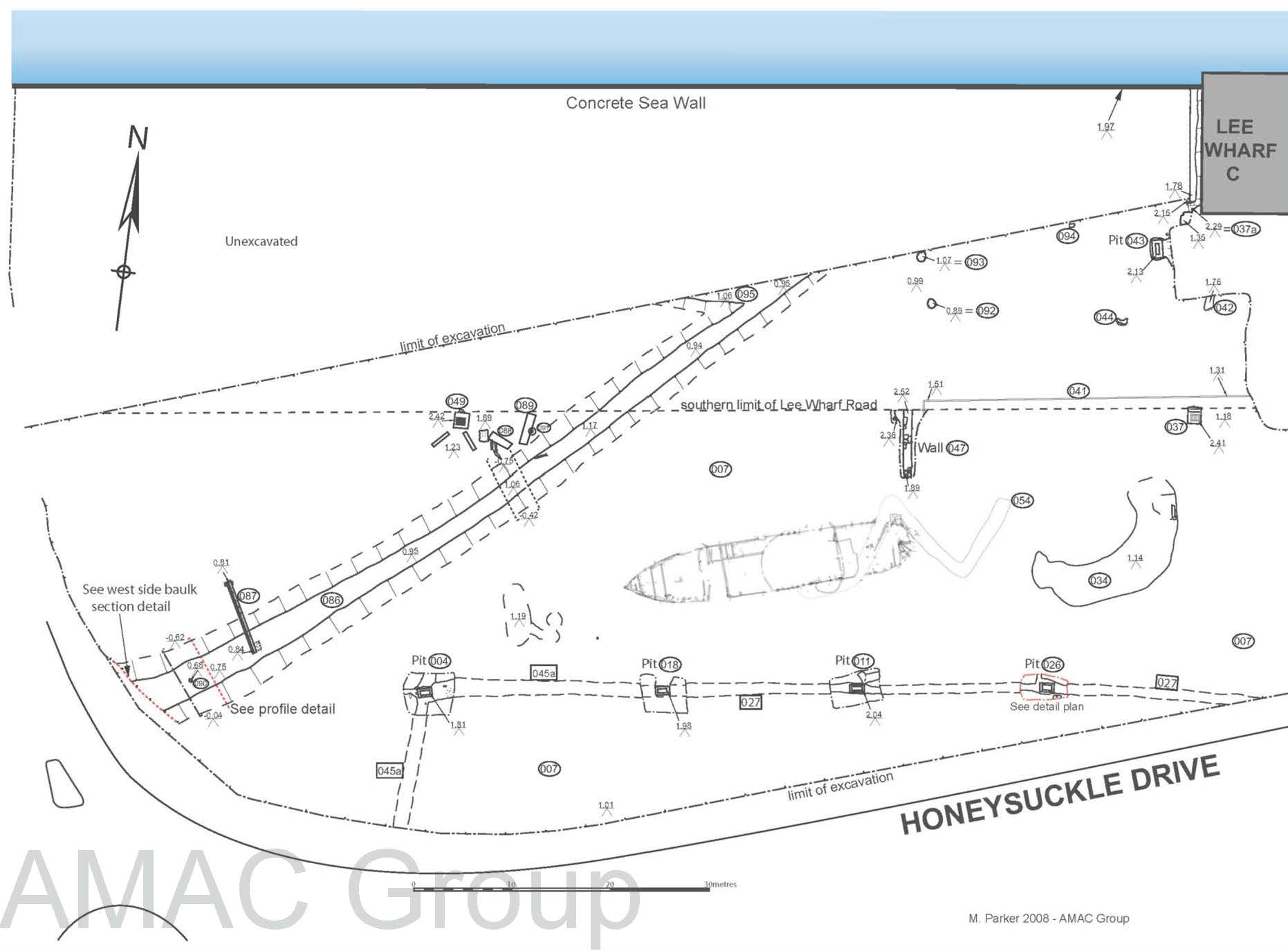

From the background research, the archaeologists knew there would be evidence for the infill of the harbour, as well as potential wharves and remains of the former seawall. They were mightily surprised, however, when within the excavation trench, the remains of a boat appeared (Figure 37). 10

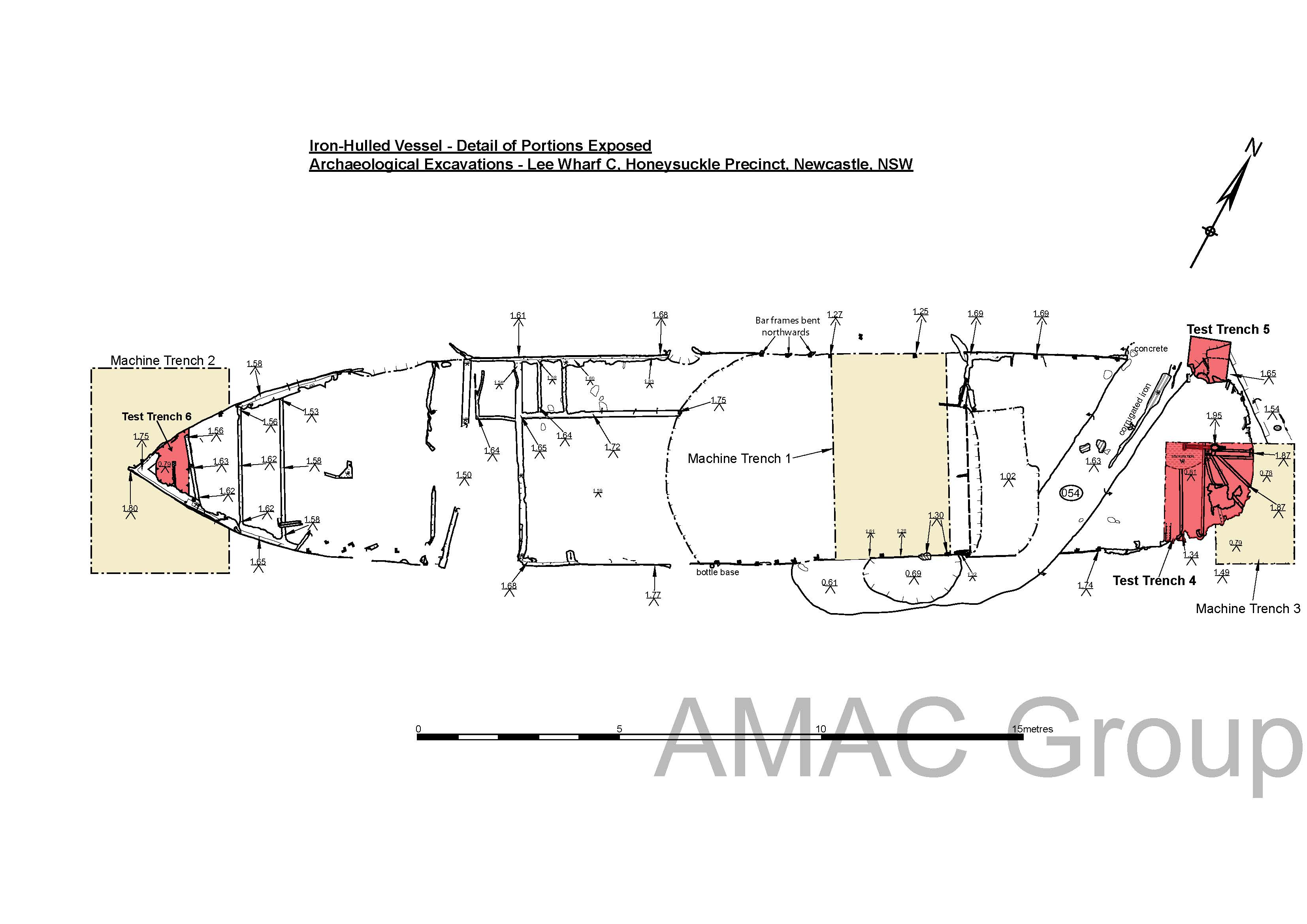

Over several weeks, machine excavation was used in combination with hand excavation techniques to uncover the boat. 11

As the sediment was excavated back, the entire boat was revealed. The archaeologists recorded the boat in meticulous detail ensuring that all of its parts were recorded.

This included the bow of the boat (Figure 43) 12 . The hull or body of the boat (Figure 44) 13 , as well as the stern (Figures 45, 46 and 47) 14 . The top of the rudder was identified, along with various steering elements, as well as chains which were used for mooring the boat (Figure 48) 15 . This meticulous recording allowed for the excavated ship to be identified with the length, breadth and depth of the boat matching the historical records of the Leo along with the round counter stern and single mast.

While lost for almost 100 years, the Leo – Newcastle’s loyal single masted paddle steamer tug boat once again took the spotlight and illustrated the region’s rich maritime history (Figure 49). 16

Archaeological images kindly provided by:

The Palais Archaeological Site

Today the site of a fast-food restaurant, this place has a long and fascinating history.

Before Newcastle was built, historic maps show the Hunter River being much closer than it is today (Figure 50 and Figure 51).1 7

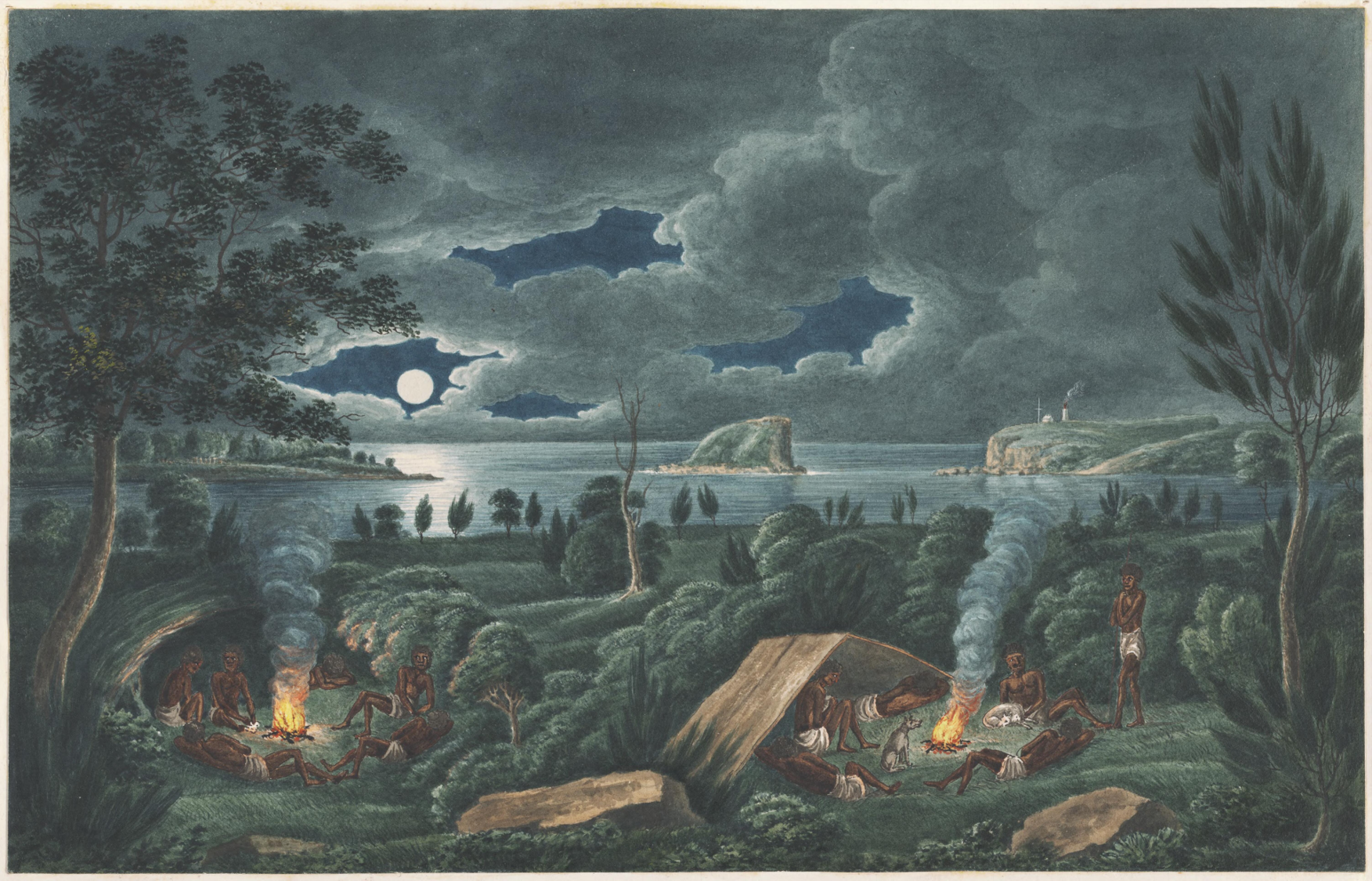

The area was abundant in wildlife (Figure 52) 18 and was an important camping location and natural resource area for the Awabakal Aboriginal people Figure 53). 19

We know Aboriginal people camped at this location due to the rich archaeological assemblage that was uncovered, which was carefully excavated over several weeks (Figures 54, 55 and 56). 20

The site showed a number of occupation layers which could be seen in the different coloured soils which spanned the site (Figure 57 and Figure 58) 21 , with the oldest levels dating back 6500 years, earlier than the pyramids in Egypt.

We can know how old these layers are using optical stimulated luminescence, a technique used on soil samples, that in basic terms, measures the last time the sample was exposed to light.

Over 5,000 Aboriginal artefacts were recovered from the excavations including backed artefacts, carefully manufactured stone points, often used to make spears (Figures 59 and 60) 22 and scrapers which were a multi-functional tool sometimes used like knives or attached to handles and used like modern day chisels (Figure 61 and 62) 23 . The majority of these Aboriginal stone artefacts were made from a local rock known as tuff, a type of rock that can be seen today in Nobby’s headland, and along Nobbys Beach

Aboriginal occupation of this area continued uninterrupted until the early 1800s as a result of European colonisation (Figure 63) 24 . The Europeans built a cottage beside the creek, and from then on, the area became known as Cottage Creek. At this time, Cottage creek was far from the Newcastle town centre and was predominantly used for farming.

Newcastle was made a free settlement in 1823, and around this time, missionary Lancelot Threlkeld (Figure 64) 25 lived in the cottage by the creek, and worked with the local Awabakal people and their leader Biraban to record and translate the Awabakal language.

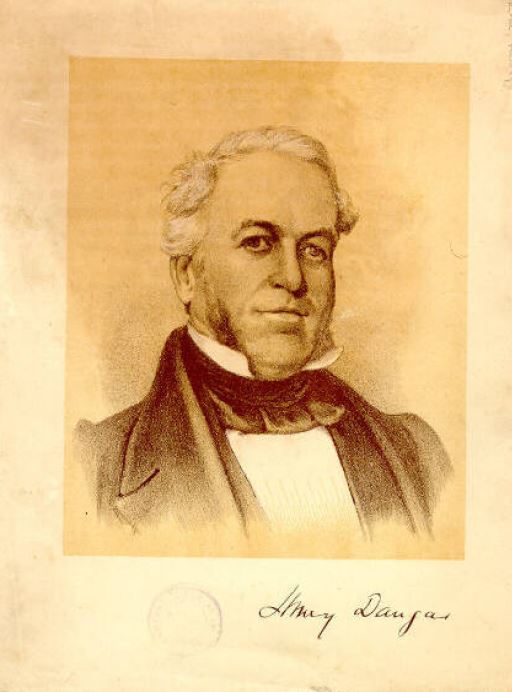

The cottage for which the area was named, ceased to be present around 1830, after being purchased by a whaler named James Weller who later sold the land to the first elected Warden of Newcastle Council, a man named A W Scott. After Scott, a business man named Henry Dangar (Figure 65) 26 owned the land, and used it from 1848 to 1855 as the location for the Newcastle Meat Preserving Company. Archaeological evidence from this period includes sheep bones, as well as some structural remains (Figure 66). 27

In the late 1800s, roller skating became a very popular activity, and in 1888 the Elite Skating Rink opened on this site (Figures 67 and 68). 28 It was a convenient location for a skating rink, with the Honeysuckle Railway Station connecting it to the rest of the city.

Unfortunately, the roller-skating fad did not last and three years later the building was converted for a more practical purpose, a market building (Figure 69). 29 It was known as the Western Markets, and it was built to mirror the Borough market in Newcastle East. Archaeological evidence from this period includes a cistern, potentially related to refrigerating goods for the market (Figure 70). 30

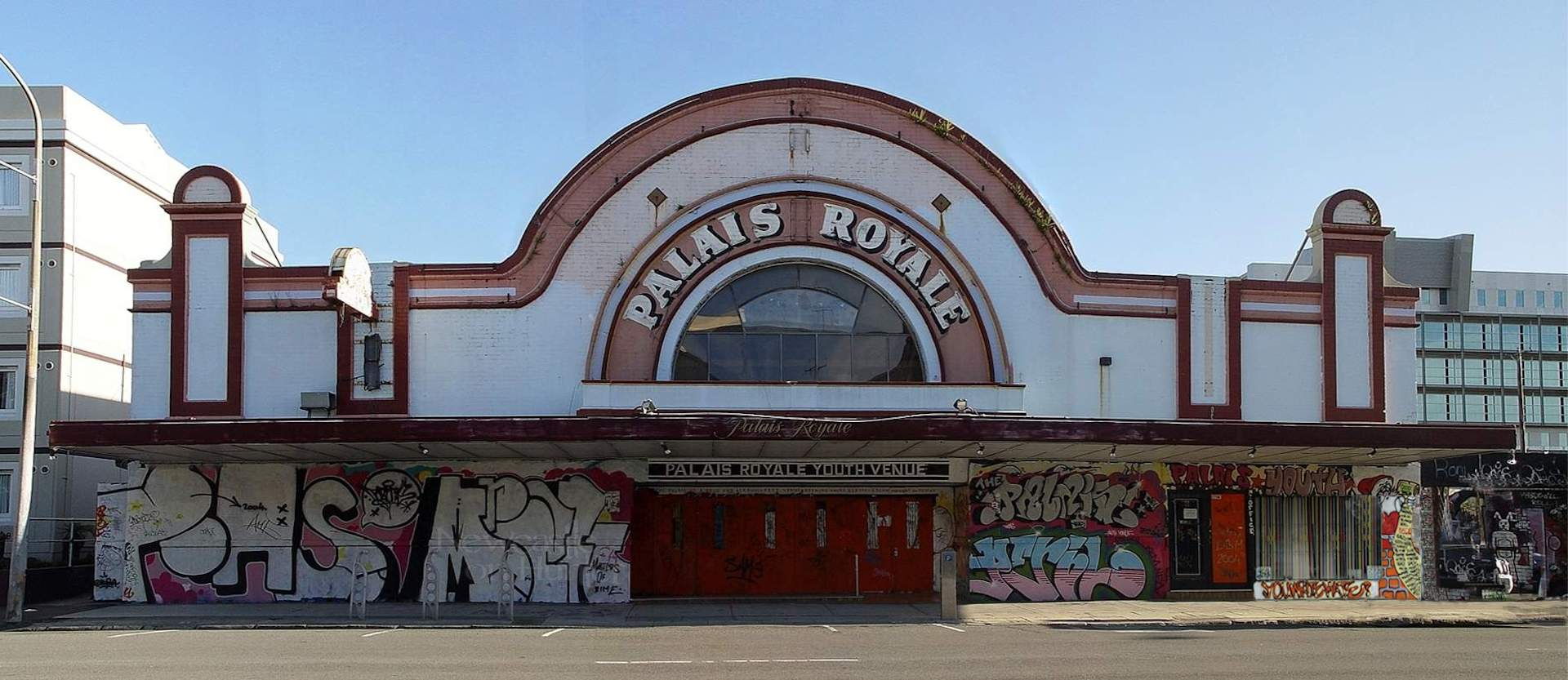

However, only another three years later the building was repurposed once again for recreation, becoming the Empire Music Hall in 1894 which then became known as the Palais Royale in the late 1920s (Figures 71, 72 and 73). 31, 32, 33

The Palais had a rich history. For over a hundred years the Palais was used for all sorts of entertainment, from hosting live music and theatre performances, to being used as a dance hall a movie theatre, and ultimately a youth venue (Figure 74)34 34 before its demolition in 2008.

Archaeological images kindly provided by:

References

Introduction

- Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 from https://hunterlivinghistories.com/2017/04/05/lycett-album/ .

Honeysuckle

- AMAC Archaeological Management & Consulting Group Pty Ltd, ‘Final Archaeological Report. Lee Wharf Project Stage 3 (a) Honeysuckle Precinct, Newcastle, NSW. Volume 1: Historical Research and Archaeological Monitoring’, 22.

- Harbours and Rivers Department, Soundings by Captain FWE Sidney, RN. Courtesy of Living Histories, University of Newcastle, Port of Newcastle , 1878. Cronshaw D. Going to the flicks in 1940s Newcastle.

- Courtesy of Living Histories, University of Newcastle, ‘Parish Map of Newcastle, 1918 (M3254)’

- Neil Baylis, Courtesy of Alamy Stock Photo, 1887 Engraving of the Paddle Steamer P.S Comet .

- ‘District News. Newcastle’.

- Courtesy of Living Histories, University of Newcastle, Poster of the United States Consular Officers, Newcastle NSW, Australia .

- Courtesy of John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, Boomerang (Ship) .

- Norm Barney Photographic Collection. Courtesy of Special Collections, University of Newcastle, BHP Steelworks Newcastle, 1915 .

- AMAC Archaeological Management & Consulting Group Pty Ltd, ‘Final Archaeological Report. Lee Wharf Project Stage 3 (a) Honeysuckle Precinct, Newcastle, NSW. Volume 1: Historical Research and Archaeological Monitoring’.

- AMAC Archaeological Management & Consulting Group Pty Ltd.

- AMAC Archaeological Management & Consulting Group Pty Ltd.

- AMAC Archaeological Management & Consulting Group Pty Ltd.

- AMAC Archaeological Management & Consulting Group Pty Ltd.

- AMAC Archaeological Management & Consulting Group Pty Ltd.

- AMAC Archaeological Management & Consulting Group Pty Ltd.

Palais Royale

- AHMS, “Palais Royale Final Excavation Report for SBA Architects” (Report to SBA Architects Pty Ltd, 2011), 42 & 45.

- Joseph Lycett, Collector’s Chest, Courtesy of State Library of New South Wales, c1820.

- Joseph Lycett, Aborigines Resting by Camp Fire, near the Mouth of the Hunter River, Newcastle, New South Wales, c1820, c1820, https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-138500420 .

- Allan Williams and Felicity Barry, “684 Hunter Street, Newcastle - Section 87/90 Aboriginal Heritage Impact Permit #1098622 Excavation Report,” Archaeological Excavation Report (Newcastle, NSW: Report to SBA Architects Pty Ltd, 2011), 52.

- AHMS, “684 Hunter Street, Newcastle - Section 87/90 Aboriginal Heritage Impact Permit #1098622 Excavation Report,” Archaeological Excavation Report (Newcastle, NSW: Report to SBA Architects Pty Ltd, 2011), 78.

- Williams and Barry, “684 Hunter Street, Newcastle - Section 87/90 Aboriginal Heritage Impact Permit #1098622 Excavation Report.”

- Williams and Barry, “684 Hunter Street, Newcastle - Section 87/90 Aboriginal Heritage Impact Permit #1098622 Excavation Report.”

- Joseph Lycett, courtesy of Newcastle City Library, Newcastle, New South Wales, c1816.

- Courtesy of Living Histories, University of Newcastle, Reverend Lancelot E Threlkeld, Mid-1800s, accessed September 29, 2022, https://livinghistories.newcastle.edu.au/nodes/view/6015 .

- AHMS, “Palais Royale Final Excavation Report for SBA Architects,” 46.

- AHMS, 143.

- Ralph Snowball, Courtesy of Living Histories (University of Newcastle), Elite Skating Rink, n.d, https://livinghistories.newcastle.edu.au/nodes/view/45947?keywords=skating%20palais&type=all&highlights=WyJza2F0aW5nIiwicGFsYWlzIl0=&lsk=11446c51f473755ee39e3416dc7a2016 .

- Ralph Snowball, Courtesy of Living Histories (University of Newcastle), Elite Skating Rink, n.d, https://livinghistories.newcastle.edu.au/nodes/view/45947?keywords=skating%20palais&type=all&highlights=WyJza2F0aW5nIiwicGFsYWlzIl0=&lsk=11446c51f473755ee39e3416dc7a2016 .

- AHMS, “Palais Royale Final Excavation Report for SBA Architects,” 69.

- Newcastle Sun, Courtesy of Living Histories (University of Newcastle), Police and Ambulance Ball at Palais Royale, Newcastle, September 13, 1933, https://livinghistories.newcastle.edu.au/nodes/view/76415 .

- Ray Perkins Collection, Courtesy of Newcastle City Library, Empire Palais , March 1931.

- Courtesy of Newcastle City Library, Palais Royale Poster Advertising Performance by The Flying Pickets, n.d.

- Phil Voysey, Palais Royale , November 13, 2004, https://www.newcastleonhunter.org/ .